Professor John Long (third from right, rear) and Rutgers Business School students with Warren Buffett.

Business Insight: Has Warren Buffett lost his touch?

John Longo, a professor of professional practice in finance and economics, co-wrote this article with his son Tyler. They are also the co-authors of Buffett's Tips: A Guide to Financial Literacy and Life, Wiley, 2020.

The short answer is “No.” The “Oracle of Omaha” is poised for a dramatic comeback since his style of investing has been out of favor the past few years, but is starting to rebound. For the final act of Buffett’s storied investment career Berkshire Hathaway has accumulated an enormous cash pile of roughly $140 billion to put to work, minus the $20 billion he likes to keep in a “rainy day” fund.

The Importance of Temperament

A good part of the reason for Buffett’s massive investment success is due to his temperament and patience. He once said, “The most important quality for an investor is temperament, not intellect. You need a temperament that neither derives great pleasure from being with the crowd or against the crowd.” Buffett calls marching to the beat of your own drummer following your “Inner Scorecard.” It’s something he learned from his father, Howard Buffett. Examples of Buffett’s ability to ignore the crowd noise are too numerous to mention, but here are a couple to illustrate our point. In 1963 he put a gargantuan 40% of his fund’s assets in a single stock, American Express, after they were embroiled a scandal financing a fraudulent salad oil company. In the aftermath of the Great Recession he scooped up stock in Goldman Sachs, General Electric, and later Bank of America. Each of these investments turned out to be big winners.

The Importance of Patience

In Buffett’s 1997 letter to Berkshire Stockholders he provides a great example of the importance of remaining patient while discussing the batting strategy of Ted Williams, arguably the greatest hitter in major league baseball history. He writes:

"…we try to exert a Ted Williams kind of discipline. In his book The Science of Hitting, Ted explains that he carved the strike zone into 77 cells, each the size of a baseball. Swinging only at balls in his "best" cell, he knew, would allow him to bat .400; reaching for balls in his "worst" spot, the low outside corner of the strike zone, would reduce him to .230. In other words, waiting for the fat pitch would mean a trip to the Hall of Fame; swinging indiscriminately would mean a ticket to the minors.

If they are in the strike zone at all, the business "pitches" we now see are just catching the lower outside corner. If we swing, we will be locked into low returns. But if we let all of today's balls go by, there can be no assurance that the next ones we see will be more to our liking. Perhaps the attractive prices of the past were the aberrations, not the full prices of today. Unlike Ted, we can't be called out if we resist three pitches that are barely in the strike zone; nevertheless, just standing there, day after day, with my bat on my shoulder is not my idea of fun."

The stocks that led the market rally over the past few years, except for Apple, were are outside of Buffett’s strike zone or sweet spot; what he calls his circle of competence. Apple is a fairly recent addition to Berkshire’s portfolio since Buffett has come to view it as a consumer stock and not a technology stock. The former sector is well within Buffett’s circle of competence, while the latter is outside of it since he says he doesn’t understand how technology will evolve over time. Our sense is one of Buffett’s lieutenants initially purchased Apple and then Buffett supersized the position as he became increasingly comfortable with the iconic firm’s superb economics.

Buffett Last Lagged the S&P 500 This Badly During the Internet Bubble

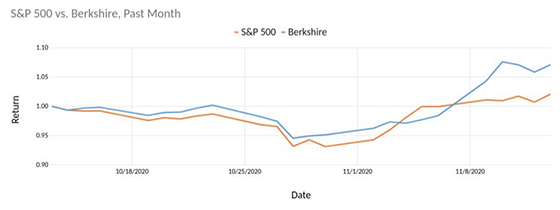

Berkshire is one of the few successful conglomerates left in the world, operating across a range of diverse industries, including Insurance, Railroads, Utilities, Aerospace, Investments, Real Estate, and Confectionery. Accordingly, it is somewhat of a proxy for the U.S. economy which is recovering from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, but not yet back to January 2020 levels. Technology stocks have led the rally over the past two years, especially since the pandemic hit the U.S. in 2020Q1, leaving diversified companies like Berkshire behind, as shown in the graph below. Over the past roughly 2 years, the S&P 500 has increased 43% (plus dividends), while Berkshire, which does not pay dividends, has only increased 12%.

An underperformance of more than 30% would get many money managers fired. But, it happened before to Buffett during the late 1990s while the Internet Bubble was inflating. In 1999, Berkshire lost 19.9%, while the S&P 500 soared 21%, an underperformance, or negative alpha in industry speak, of more than 40%! Over the next 3 years, 2000-2002, the S&P 500 lost 37.6%, while Berkshire made 29.7%, a 3-year cumulative alpha of more than 60%! There are a number of differences between the Internet Bubble and the current market. Perhaps the most important distinction is the FAANG stocks that rule the current market are companies with dominant positions and sustainable profits, while many of the Internet Bubble leaders, such as AOL, JDSU, and ICGE, were speculative. A comparison of FAANG to the Nifty 50 stocks from the 1960s-1970s is more apt.

Berkshire Is Starting to Rebound

It is hard for many to fathom that broad stock indexes in the U.S. are up roughly double-digits this year while we are dealing with the worst pandemic since 1918 and a badly damaged economy. Part of the disconnect between stock market performance and the economy is because the market is a forward-looking mechanism. As bad as things may be today with COVID-19, market participants see light at the end of the tunnel with a vaccine and improved therapeutics on the horizon. Additionally, “stay at home” stocks, such as Amazon.com, Microsoft, Alphabet, Home Depot, and Apple have an outsized impact on the S&P 500’s returns and are all up strongly year to date. Although the S&P 500, a market capitalization weighted index, is up for the year, the median stock is down.

As market participants see light at the end of the long COVID tunnel, Berkshire has started to rebound. Over the past month, Berkshire has increased roughly 7% vs. 2% for the S&P 500, as shown in the graph below.

Opportunities Exist and (Berkshire’s) Cash Is King

Although the public knows Buffett as a value investor, he actually dislikes the labels of growth and value. He thinks the growth-value dichotomy is a misnomer, believing all investors are value investors since they all they seek to buy undervalued assets. He argues growth is merely one component of the value equation, but we’ll leave the details of that calculation for another day. However, what is clear is that Buffett doesn’t like to overpay for his purchases. In case you are wondering why Buffett didn’t pounce during the depths of the March/April lows, a Bloomberg article cites the Federal Reserve beating him to the punch by flooding the market with cheap money, making Berkshire’s more expensive capital less desirable despite its sterling imprimatur.

Using a simple screen of large, profitable companies selling at a material discount to the market we find ample opportunities for Buffett and his two co-managers, Todd Combs and Ted Weschler, especially given their growing pile of $140 billion in cash. Specifically, our screen looks at companies with a market capitalization of at least $10 billion, a forward P/E of < 15, an operating margin > 25%. Buffett also likes companies with a wide moat, which we don’t include in our screen. (In case you are curious, Morningstar has done some research on identifying companies with moats and rates them accordingly.) We found 51 companies that met these hurdles, including AbbVie (a new holding), Amgen, Cisco Systems, Discover Financial Services, eBay, GlaxoSmithKline, Intel, J.P, Morgan (a current holding), Merck (a new holding), Oracle, Philip Morris, Sanofi, State Street, and several others. Of course, there are millions of private companies out there as well, some of which are quite large. Indeed, Buffett’s preference is to buy good companies in their entirety, since he can roll them into Berkshire as a subsidiary and let their earnings compound.

Berkshire Is Selling Near the Lower End of Its Historical Valuation Range

If you want to see a puzzled look on someone’s face, tell them that you know of a $350,000 stock that appears to be undervalued. Of course, we are talking about Berkshire (Class A), but for the uninitiated, there is also Class B (BRK-B) which differs only in voting rights and sells for a far more palatable $225 a share. Buffett’s preferred method of valuing an investment is a technique called intrinsic value, which attempts to measure the current value of a firm’s future cash flows. Wall Street analysts often use techniques of relative valuation, since it is less reliant on assumptions and avoids sensitivity problems.

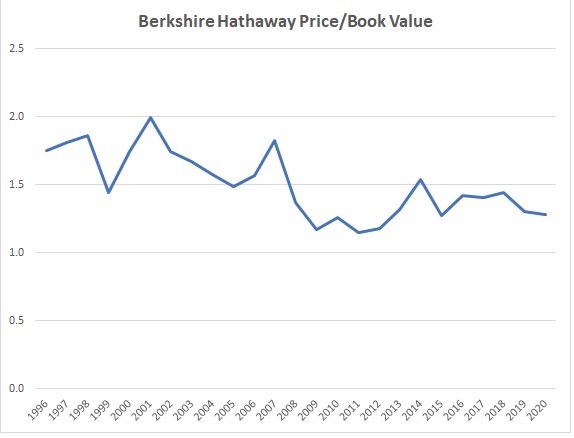

Analysts historically valued Berkshire as a multiple of its accounting or book value, due to the outsized role of its insurance businesses in the firm’s profitability. The assets of many financial firms are its loans and insurance policies. Account holders never knowingly pay more than the face value of their loans, so book value can often be a rough approximation of value for many financial stocks. Strong financial firms, such as Morgan Stanley, usually sell at modest premium, such as 20% to 25% to book value. In contrast, technology, healthcare, and consumer staples firms often sell at sizeable multiples of their book values since the brand names and intellectual property often dwarf the historical accounting (book) value of their assets. For example, Moderna, developer of a leading COVID-19 vaccine, is selling at a huge multiple of its book value since the potential cash flow from vaccinating a sizeable part of the world for the foreseeable future far outstrips their historical R&D and other relevant costs. Below is a graph showing Berkshire’s price to book value over the past 25 years.

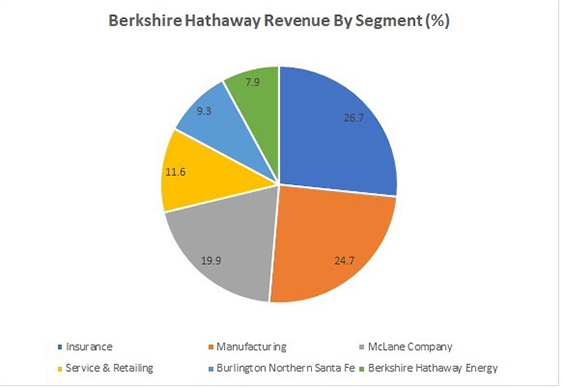

Not only does the stock appear inexpensive on a Price / Book basis, but the evolving nature of Berkshire’s subsidiaries and profit mix suggest that it should sell at a premium to its prior book values. This observation helps explain why Buffett doesn’t include Berkshire’s book value on the cover of its annual report anymore, while it regularly did in years past. Today, insurance accounts for roughly 25% of Berkshire’s business, relative to a 75% figure 25 years ago. The pie chart below shows revenue for each of the main Berkshire segments in 2020.

An average of publicly traded Railroad, Utility, Food Service, Manufacturing, and Service / Retailing, competitors trade at 7x, 2x, 3x, 4.5x, and 3.5x book values, respectively. Using an earnings multiple analysis, rather than a book value, yields similar results. Combined with Berkshire’s investments in external companies and net cash, on a sum of the parts basis, the stock appears to be selling at a discount to its intrinsic value. We’re purposely not putting a price target on Berkshire, but you can do the math yourself and note our disclosure at the bottom of the report.

The Market Multiple on Value Stocks May Increase, Resulting in an Additional Tailwind

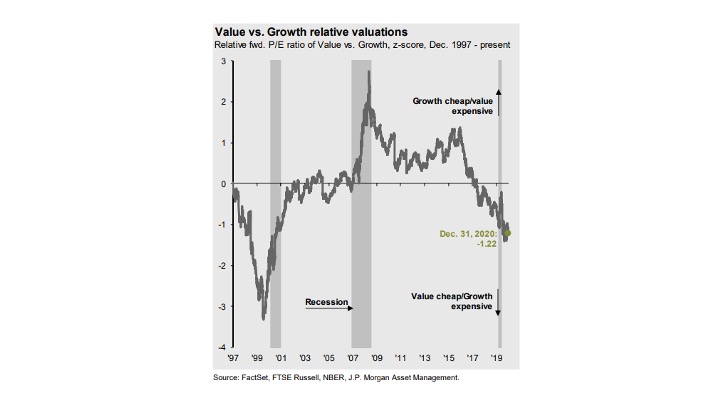

The type of businesses which comprise Berkshire and the types of stocks Buffett likes, which for lack of a better term called we Value stocks, are trading at very depressed levels relative to their historical values. By definition, Value stocks sell at lower multiples than Growth stocks, but the relationship of this ratio vacillates over time, as shown in the following graph.

The last time Value stocks were this unloved or hated was during the Internet Bubble. As fear dissipates once COVID-19 slowly becomes something we learn to live with, Value stocks may not be left for dead anymore, sowing the seeds for their recovery. So, not only is Berkshire selling below its historical values, but the multiples of its value peers are depressed as well, creating a double whammy effect, if things normalize. Putting it all together we think Buffett and Berkshire are poised for a rebound and can’t wait to see how he and his colleagues put that mountain of cash to work as he enters the twilight of his illustrious investment career.

Disclosure: John Longo and Tyler Longo both own shares in Berkshire Hathaway.

Disclaimer: This article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. No recommendations are made with respect to the purchase, holding, or sale of any securities. Nearly all investments contain risk and may result in substantial losses.

Press: For all media inquiries see our Media Kit