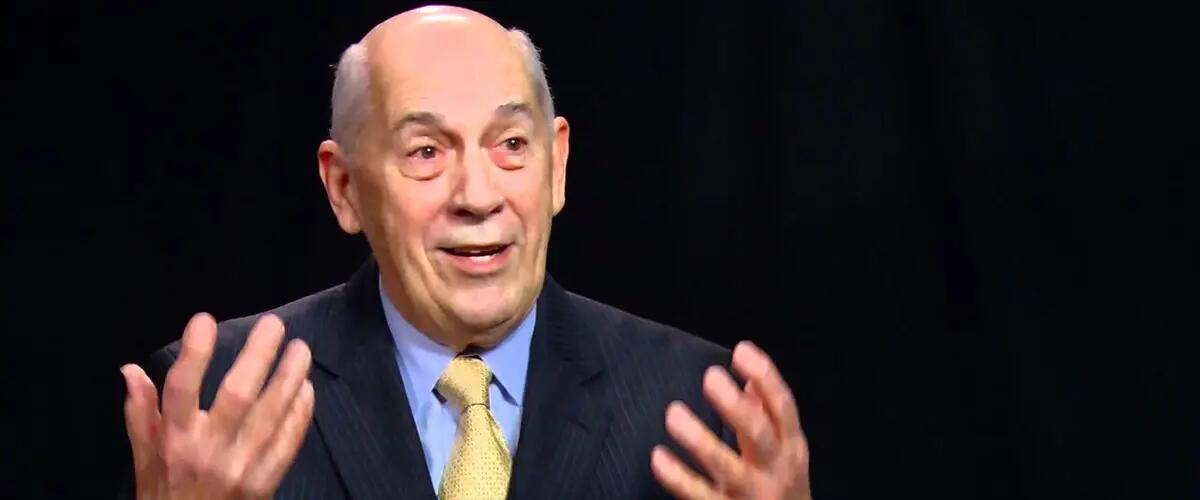

ESPN founder Bill Rasmussen graduated from Rutgers’ MBA program. Photo: Courtesy of Bill Rasmussen.

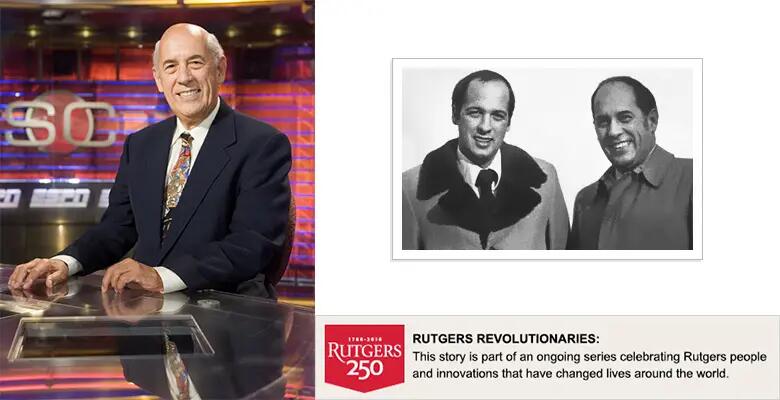

Bill Rasmussen: Rutgers MBA alumnus founded ESPN, created first 24-hour TV network

By Amber E. Hopkins-Jenkins

This story was originally featured in Rutgers Today, part of the Rutgers Revolutionaries series to celebrate the university's people and innovations that have changed lives around the world.

Without Bill Rasmussen’s fanaticism for sports and his entrepreneurial spirit, the world might not have SportsCenter or wall-to-wall coverage of March Madness and the College World Series.

Rasmussen changed not only sports broadcasting but also how the world watches television when he founded ESPN, which became the world’s first network to broadcast around the clock when it went live on September 7, 1979.

“You have to remember that there was no CNN, no Fox News, no MTV,” says Rasmussen, who also served as the network’s first president and CEO. “And the networks would sign off for six hours at night.”

Rasmussen grew up on Chicago’s South Side before attending DePauw University for undergraduate study and spending two years in the Air Force near the end of the Korean War. He enrolled in Rutgers’ MBA program while working for Westinghouse and graduated in 1960.

The self-proclaimed “sports junkie” became a local sports anchor for television stations in Massachusetts and Connecticut during the 1960s and 1970s. He was always frustrated by the amount of time he had – or didn’t have – for sports news during broadcasts.

“I typically had about three minutes to give highlights and that was limited to mostly professional sports. There wasn’t much time to discuss college sports or teams outside the area,” Rasmussen says.

He believed 30 minutes would be sufficient to report sports news and thought lesser known sports and teams could gain traction with the viewing population. This insight would eventually lead to the launch of SportsCenter, which remains ESPN’s flagship program and features daily sports news opposite typical evening news broadcasts.

Rasmussen was communications director for the New England Whalers, a professional ice hockey team, in 1978 when he and most of the front office staff, including his son Scott, were laid off when the team didn’t make the playoffs. The lifelong entrepreneur had an opportunity to pivot his career and did he ever.

He’d always enjoyed broadcasting and a local cable operator suggested contacting RCA to learn more about a satellite. The RCA representative discussed several available satellite packages, including a 24-hour package that no one had ever purchased.

“I had no idea what all the technical satellite terms meant, but I knew it would give us 8,760 hours a year of television programming,” he says. “We didn’t have money for the transponder, but there was a clause in the contract that didn’t require us to make our first payment until 90 days after our first use of the satellite. So we just took it and figured it out.”

In August 1978, the Rasmussens were stuck in traffic on I-84 while driving from Connecticut to the Jersey Shore and took the opportunity to brainstorm ideas to fill those 8,760 hours.

“Scott said something like, ‘Play football all day for all I care,’ and the ideas started flowing fast and furious. Sports fans are always hungry for sports. We knew they’d be hungry for the content because… we’re sports fans.”

Rasmussen went out to pitch the idea to cable television companies, investors, sponsors and partners. He says they were bombarded by naysayers who doubted the viability of a 24-hour, single-niche network.

“Many told us the idea wouldn’t work, that it wouldn’t be able to sustain itself. Some said cable would be gone in a few years.”

He met with – and was turned away by – many potential investors until Getty Oil said "yes" in February 1979. By that spring, the network had secured its first advertising agreement with Anheuser-Busch.

Having secured the satellite, investors and advertisers, Rasmussen was ready to meet with the NCAA to discuss airing its Division I men’s basketball tournament. Though NBC had the national contract for the tournament, it only aired the Final Four and a few regional games. ESPN was given the opportunity to air all the rest of the games in the tournament, now known as “March Madness,” in 1980.

Steven Miller, a journalism professor at Rutgers’ School of Communication and Information, says there are now courses on critical issues in sports media and sports journalism specializations at universities because of ESPN.

“Rasmussen’s brainchild elevated sports from the sidelines of the nightly newscast and made it palatable for every demographic, not just the fanatics,” says Miller. “ESPN equals sports worldwide. The network transcends the sports and cable niches and is a global cultural phenomenon and brand.”

Visionary

Miller considers Rasmussen “a true visionary” who understood the impact of sports on society and saw sports as entertainment.

“What Rasmussen and his son dreamt up during that car ride to the Jersey Shore changed the landscape of sports, television, cable television and advertising. That’s revolutionary thinking.”

Today, ESPN encompasses eight U.S. and 24 international television networks among its more than 50 business entities. If you have watched the NBA Finals or other sports programming on ABC, you will have seen the ESPN brand.

Rasmussen was honored by Sports Illustrated as one of the 40 individuals who had the greatest impact on the world of sports in the second half of the 20th century.

Though he hasn’t been on staff since June 25, 1984 (“At 2:05 p.m.,” he recalls.) when ESPN was sold to ABC, Rasmussen, now 83, believes ESPN is still the same product in essence; it’s simply delivered on many more platforms, he says.

“The underlying culture has been evident since day one: stay laser-focused on the mission to serve sports fans anytime, anywhere. It’s all about sports. It will always be about sports. Every decision is driven by sports.”

Press: For all media inquiries see our Media Kit