Getty Images

Thought Leadership: 5 things supply chain managers can do to contribute to humanitarian relief

This article by Iana Shaheen and Arash Azadegan was first published in Supply Chain Management Review on March 28, 2023.

The earthquake that devastated parts of Turkey and Syria earlier this year presented yet another challenge for supply chain managers attempting to expediently deliver humanitarian relief. And, unfortunately, it won’t be the last opportunity. There will be more earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, fires, and droughts, not to mention disasters of the human-made type like wars and industrial accidents.

The private sector often is well-positioned to respond with supplies, money, and expertise, and supply chain managers are at the forefront of these efforts.

Indeed, corporations can be better positioned than governments or nonprofits to help disaster victims with supplies, money, and expertise. Such was the case in 2005 with the response of Walmart’s Emergency Operations Center to Hurricane Katrina.

Firms like Walmart, Amazon, UPS, FedEx, and DHL employ many of the world’s top logistics and supply chain experts who oversee global networks day in and day out and have access to cutting-edge tools for managing the flow of goods.

Fully maximizing these capabilities requires partnering with public agencies, but those partnerships often are never forged or are ineffective.

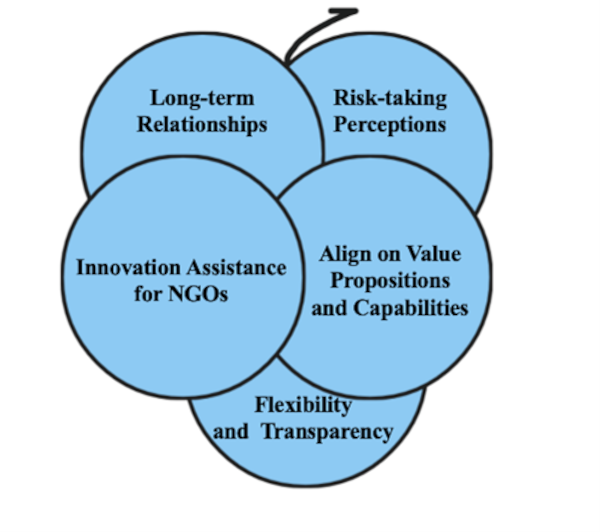

In researching disruptions in supply chains and the dynamics of humanitarian supply chains, we’ve identified five key lessons for private-sector supply chain managers when working with government agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

1. Develop long-term relationships before disasters strike.

Timing is critical during a disaster, and the best response is to immediately allocate people, supplies, and equipment to the front line rather than trying to decide what to do and how to do it. Organizational confusion should not add to the inevitable chaos that comes with a disaster. Developing information channels, operational procedures, and asset management on the front end makes the response more effective from the beginning.

Government and NGO managers who focus on humanitarian relief are constantly involved in disaster preparation—developing contingency plans, prepositioning essential emergency items, ensuring proper emergency training, and building capacity. The sooner the private sector joins in those efforts, the better.

The Ikea Foundation, for instance, had been working with Better Shelter for more than a decade when earthquakes hit Syria and Turkey. So, the foundation immediately agreed to financially support the NGO, which makes flat-packed shelters that volunteers can raise in a few hours. But there was a logistical challenge of getting the shelters from a warehouse in Poland to the devastated areas. Ikea mobilized 36 trucks (its own and from partners) to help move about 5,000 units to Turkey in days rather than months.

NGOs provide critical competence and capacity when it comes to coordinating long-term relationships. During a disaster, they provide experienced responders; in downtimes, they plan and coordinate for the next call to action.

Critical to this preparation is becoming familiar with other organizations, including corporate partners. Unlike partners in commercial supply chains that regularly interact, humanitarian relief groups may engage with each other only during actual disasters. In other words, advance work on relationships can help identify with whom and what one should become familiar.

It’s worth noting that different types of organizations often view their relationships with others differently. Our research, for example, found that local NGOs tend to take a communal (nonreciprocal) view of their relationship with others, while national NGOs see them as an exchange (reciprocal). Government agencies, whether local or regional, typically take a hybrid view. During a disaster response, there’s a general shift toward communal and away from exchange relationships.

The challenge of building key relationships in the right way is aided by organizations like the American Logistics Aid Network (ALAN), which helps connect industry expertise and resources with nonprofits so the NGOs can fulfill needs more quickly and efficiently.

2. Align on value propositions and capabilities.

It is important that humanitarian organizations and private-sector contributors align on what each party values and how its capabilities help achieve what it deems important.

The idea that the partnership will “serve the greater good” is only a starting point. A deeper understanding of values and capabilities helps determine if the partnership is truly a good fit.

National NGOs typically value direct economic incentives (similar to private organizations), whereas local NGOs tend to be more interested in indirect or intangible incentives. A large, national nonprofit, for instance, might expect to benefit from the media attention it gets with a partnership, while a local organizationFe may care more about community impact.

Private-sector organizations need to consider these factors and fashion their value propositions to match the NGOs’ expectations. A local business might see value in donating to earthquake relief in Syria and Turkey, but it also should consider partnerships with local schools, shelters, or other organizations that align with its values. The time, money, or expertise it can offer, in fact, might have a bigger impact at home than on the world scale because of local knowledge and relationships.

Consider a sporting goods store in a small town in mid-America. If it wants to donate shoes or soccer balls, just about any NGO would take them. But, if a working relationship is in place with a local nonprofit that actually needs shoes or soccer balls, store ownership/management can be certain they are making a positive impact by giving what’s needed, where it’s needed, and when it’s needed.

On the other hand, the Elon Musks of the world who can provide technology to restore internet access in Ukraine are probably better positioned to donate globally than locally.

Of course, it’s not an either/or dilemma. Companies (and individuals) can and should assist at local, national, and global levels. But aligning on values and capabilities helps them decide how to best distribute their giving.

3. Risk-taking and perceptions are different among NGOs than in the private sector.

The context, task, and structure of an NGO is a strong determinant of how risk-taking is viewed and practiced in humanitarian relief, and leaders in the private sector should adjust their expectations accordingly.

Risk-taking, for instance, is embedded in the thinking of community-based organizations; therefore, expecting them to practice extreme caution may not be realistic. Similarly, managers working for established organizations (police, firefighters, or FEMA) should recognize that the strong influence of standard operating procedures can be an inhibitor.

Some corporations have teams that work only on disaster relief and employee volunteers who respond when a crisis strikes. But risk-taking levels differ between, say, a corporate truck driver, a utility worker, a firefighter, and a volunteer from a church. Failing to understand and address these differences can put private-sector volunteers in unreasonable situations or exclude them from jobs they are capable of handling.

Our research also found that risk-taking can shift depending on the type of NGO and the disaster response stage. Expanding organizations (e.g., primary disaster-response NGOs) are generally risk-averse during the immediate response stage but become risk takers during the short-term recovery stage. In contrast, extending organizations (e.g., homeless shelters) are risk-taking during the immediate response but become risk-averse during short-term recovery.

4. NGOs need help with innovations.

NGOs are constantly looking to collaborate with external partners who can contribute resources and expertise that yield better results. And developing social innovation does not have to involve costly endeavors for private-sector partners. Making do with what is readily available by creating and reallocating existing resources can prove highly effective.

In some cases, innovation can develop in the moment as NGOs and private-sector partners deal with the immediate needs of a crisis, as with Ikea’s work with Better Shelter.

Innovations also can address long-term needs. For instance, the hunger-relief organization Philabundance joined with local partners in 2013 to open and operate a nonprofit grocery in Chester, PA, a city that hadn’t had a supermarket since 2001 and where food scarcity had become a concern. It was a complex and untested business model, but it worked—in part because of multiple partnerships that provided the organizational capabilities and resources needed for developing social innovation.

Historically, the private sector has played a reactive role in innovations for NGOs: A nonprofit takes an idea to a corporate partner, who helps make it a reality if they can. More companies, however, need to take the initiative by evaluating their capabilities and applying them to humanitarian problems, even before they are asked.

A software firm, for example, might devise ways to improve operations of the nonprofits it supports. Likewise, a restaurant staff might teach classes on cooking to residents of a local shelter.

A farm in Florida showed this type of initiative when it partnered with a food bank to develop raised-bed gardens, then taught employees and volunteers how to better grow and harvest the fruits (and vegetables) of their labor. For a small expenditure, they helped the food bank establish its own source of food. It was a low-cost, high-impact innovation.

5. Be transparent and allow flexibility.

Every nonprofit has administrative costs. Without directing adequate funds to these needs, the organization can struggle to operate effectively, even when it has a surplus of resources.

Companies, like individuals, should do their due diligence when deciding who to partner with and how to structure their donations. Such research should go deep enough to reveal why the administrative costs of one organization might legitimately be higher than another.

NGOs, of course, need to be transparent about their operations and their needs so that private-sector partners are well informed and willing to make contributions that allow for flexibility in how they are used.

In some ways, this goes back to understanding the value proposition of the NGOs. Nonprofits often measure success differently, and it’s not always possible to achieve the same levels of efficiency and effectiveness that are standard in for-profit practices.

Each humanitarian organization’s key performance indicators (KPIs) also differ based on mission and goals. Feeding America measures how many people it can feed per dollar donated ($1 = 10 meals). The Salvation Army calculates how many shelter beds it can provide for a dollar. A mental health clinic, meanwhile, would assess how many people it can help per year—a metric that is complicated by the length of time it can take to see results.

The need to develop better public-private partnerships for meeting humanitarian needs is significant because of the sheer volume of challenges. From 2000 to 2019, for instance, the United Nations reports there were 7,348 recorded disasters resulting in more than 1.2 million deaths and trillions of dollars in economic loss. That doesn’t include non-disaster problems like homelessness and mental health issues, or the compounding effects from COVID-19. The resources and expertise in the private sector—especially in supply chains and logistics—are critical to moving aid to the people who need it. And that only happens with effective partnerships.

About the authors:

Iana Shaheen is an assistant professor of supply chain management in the Walton College of Business at the University of Arkansas. Arash Azadegan is a supply chain professor at Rutgers Business School and manages the Supply Chain Disruption Research Laboratory (SCDrl) at the Center for Supply Chain Management.

Press: For all media inquiries see our Media Kit