Fitch downgrade of U.S. will force rethinking of future economic policies

GOODBYE KEYNES, HELLO REAGAN!

OR

WHY THE FITCH DOWNGRADE OF U.S. TREASURYS MAY ACTUALLY BE GOOD FOR THE USA

OR

QUICK! SOMEONE CALL PRESIDENT BIDEN! HIS SPENDING PLANS NEED TO BE AXED!

By Farrokh Langdana, Director, Executive MBA Program & Professor of Finance and Economics

This blog was inspired by responding to questions from students and alumni in the Rutgers Executive MBA program about the current economic and financial situation in the United States. Rutgers EMBA program has consistently ranked in the Top 3 in Economics globally by Financial Times.

For more of Prof. Langdana’s blogs please visit his Faculty Blog: business.rutgers.edu/Langdanamacro.

More than three titles professor? Isn’t this a bit excessive—even for someone as whimsical as you?

Before you know it, I may add even more titles! Macroeconomics has become too multi-faceted for just one title!

OK then. So, what happened with this Fitch downgrade (see: “Fitch Downgrades the United States' Long-Term Ratings to 'AA+' from 'AAA'; Outlook Stable”)? Isn’t U.S. Treasury debt supposed to be super-safe?

Yes indeed. In fact, it is THE safest investment on the planet; it is the benchmark “risk-free” asset!

So, what happened?

Well, “too much of a good thing is bad,” I suppose. Our Federal budget deficit is financed (partly) by borrowing from the rest of the world and from U.S. residents, in that order. This is done by the Treasury issuing (selling) very safe government debt (Treasury bonds). As long as the Federal budget deficit/GDP is under five percent, we can simply “roll over” this debt forever—in perpetuity. That is, when it comes time to pay back a lender A, Uncle Sam can borrow from B, and when it is time to pay back B, we borrow from C, and so on and on…. forever.

Wow. That’s a good deal! But what happens if the ratio exceeds five percent?

Then borrowing forever is simply not possible. (This result is derived from the Dornbusch model of deficit sustainability, see: “Langdana: Macroeconomic Policy, 4th edition, chapter 3.”) In other words, if the result is greater than five percent, then it is highly likely that the budget deficit—the excess in spending over what the government gets in tax revenues in one year—will have to be simply financed by printing money; by “monetization.”

So, what’s the problem with that?

There’s a BIG PROBLEM with that. This is how hyperinflations happen. Think Zimbabwe, think Venezuela, Sri Lanka, Weimar Republic! Imagine prices doubling every 30 minutes as they did in Post-WWI Germany!

But wait! Weren’t we at about 10-12 percent deficit/GDP during the subprime crisis of 2008-2010 and then about 15-17 percent in the Covid era, but the sky did not fall on our heads! There was no hyperinflation. What gives?

Hyperinflations actually erupt ONLY when the money that is printed—the “liquidity”– is injected into circulation into the economy. For example, by the time the money was printed (the deficits were monetized) in, say, the raging Hungarian hyperinflation, post WW2, the money was immediately thrown into circulation when (for example) the teachers and public service workers were finally paid six months late and had to make their rent payments, etc. This is why inflation in the last month of that hyperinflation was over 1015 percent! But then, for us, since the subprime recession through Covid, all the monetization just “sat there.” It was not thrown into circulation. In macro we call this a “liquidity trap.”

Zillions of printed notes of currency just “sat there” because borrowers did not want to borrow, and lenders did not want to lend due to the fact that confidence had completely crashed. Remember Covid? Nobody was going anywhere nor doing anything!

So, we got away with printing all this money and dodged high (hyper) inflation! Thanks to a Liquidity Trap, right?

Exactly! And some policymakers got complacent. Some thought that they could now spend like maniacs by printing money and there would be no adverse consequences. There was this crazy belief that, “Deficits do not matter! So why not spend away! Spend billions! Wait! Spend Trillions!” Some, breathlessly, even gave it a name: Modern Monetary Economics. (Please see my blog-page and also, “Do budget deficits "matter" anymore?”)

From Day One, Minute One, I have stressed that there was nothing modern about it and it was not a theory, but, instead, a dangerously misleading quirk of macro-economics. Budget deficits do indeed “matter.”

What’s the situation now?

Since early 2022, the Liquidity Trap has been rapidly disappearing as confidence, post-Covid, has been resurrected. The printed money, long dormant, is now rushing into circulation. After being largely absent for 40 years in the U.S., inflation has come back and is here to stay.

Regarding budget deficits, we are back to that benchmark of five percent to be sustainable. Well, it is now at around 5.7 percent (August 2023) and is predicted to get to 6.7 percent by late 2024 by some agencies. Hence the warning from Fitch to Uncle Sam (the Treasury) to take it easy with the borrowing and the spending and to start bringing its spending rate down.

Speaking of the Fitch downgrade…is this actually a good thing?

It is a timely and clear warning to Team Biden that they need to re-think their massive spending plans. They cannot keep spending and throwing money about and expect to keep borrowing from the rest of the world at the current rate. The Green Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, and all the other massive spending proposals may now have to be tabled.

The bond market is sensing inflation too. On my blog page we have discussed the Fisher Effect and how “Bonds know Best” (see: “Langdana, Macroeconomic Policy, 4th edition, Chapter 6,” and also, "Forecasting future risk and inflation using long term interest rates"). Mortgage rates are climbing. The long-bonds sniff inflation increasing again in the future due to fears of impending budget deficit monetization; long term interest rates are climbing.

That doesn’t sound good…is there a solution?

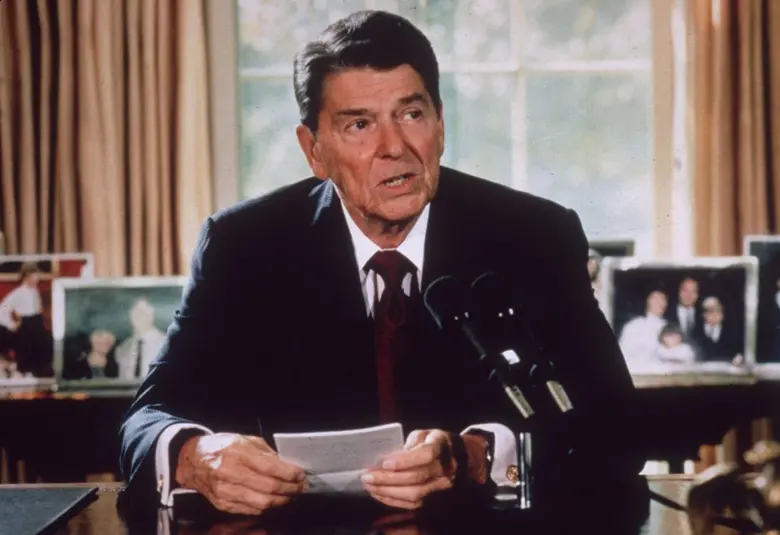

Most macro policies since 9/11 have been largely Keynesian policies characterized by large government spending and huge monetary expansion—aggregate demand-side policies. That game may be over. It is becoming rapidly clear that the days of large spending without inflationary consequences are over. It may be time to move back to the supply-side—to Reaganomics.

Really? Reaganomics.

Yup. The Supply-side. Where the smart money endogenously—organically, on its own, without government interference—decides on what kind of innovation should be funded. Which EV battery to make? What kind of Green technology to embrace? Or, as an example, to even decide if fossil fuels can realistically be replaced in our lifetime? Endogenously. Not by government degree or government exhortation.

What would be the role of government?

The role of government would be to provide for an “ecosystem” that germinates innovation—low taxes, non-intrusive regulation, free flow of smart money and smart people—and then to step back and leave us to it. This would be very "Adam Smith" indeed. Hopefully, as I have often articulated, given our long and illustrious history of innovation, we will not disappoint. Hopefully we will come up with the “next big thing” again.

But then, how do we deal with climbing inflation?

Aside from cutting back on spending plans, the obvious first step would be to shave 2-4 points off inflation right away by dismantling tariffs. In fact, the Biden tariffs are actually worse than even the trump Tariffs; there is a new proposed tariff on imported can-making metal from China, Germany and Canada which may drive up the price of cans by 30%. This is to appease the United Steelworkers Union and Ohio-based Cleveland Cliffs, owner of one of the few remaining tin-plate manufacturers in the U.S. Keep in mind that U.S. consumers pay for the tariffs! The foreign countries against whom we levy tariffs do not. We (the consumers here at home) bear the price (see: “Chapter 6 Langdana and Murphy, International Trade, Springer Press,” and see also, "Trade Wars and Their Consequences: Egyptian Cotton and Indian Tea").

Wow! So, it looks like we are headed toward a whole new ball game soon!

Yes, and you heard it here first!

What is the outlook for us in the USA?

We have been warned. We know the score. Right now, globally, we are in the best shape post-Covid. We are still one of the few “safe haven” countries in the world, along with Japan, Singapore, and Switzerland—and we always will avail of “flight to safety” capital inflows. But there is turbulence ahead. We can navigate it and we will. But only with strong leadership that does not pit us against each other. If we can again think as citizens of one country—and not as red states and blue states—we will pull this off.

OK, I feel better, professor. Final words?

Final words from Rutgers Business School, now the #1 Public Business School in the Northeast and its Executive EMBA Program, known globally as the Powerhouse:

Welcome to the Powerhouse!

Dr. Farrokh Langdana is a professor of Finance & Economics at Rutgers Business School and the director of its globally ranked Executive MBA Program—The Powerhouse. All the opinions and analyses expressed here are his, and not necessarily those of Rutgers Business School.

Press: For all media inquiries see our Media Kit